What to do with the College Football Playoff

Our Central Historical Question for the day: How do you rank a college football team?

COLLEGE FOOTBALLFOOTBALL

James Kemp

12/13/202523 min read

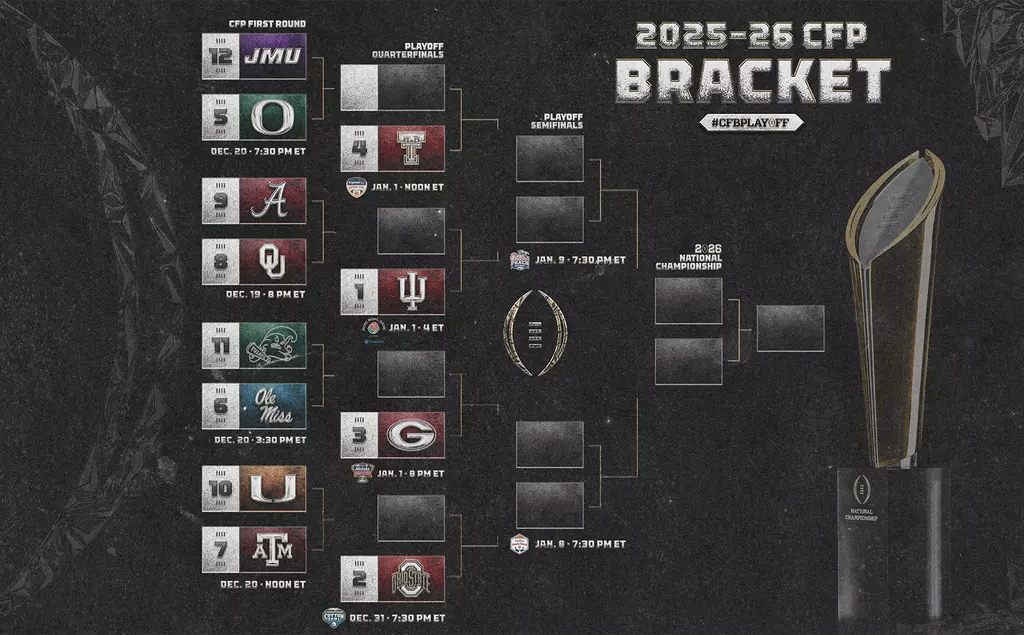

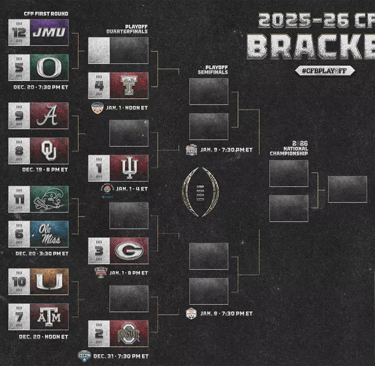

This has been a difficult and historically significant week in the history of college football. The CFP Committee left Notre Dame and BYU out of the Playoff, and the internet handled it as maturely and rationally as you would expect. There are now talks of expanding the field for next season, and even Notre Dame threatening to end their alliance with the ACC. How did we get here? What went wrong? Did we ever really get anything right?

For over a century and a half, college football has entertained the American populous with feats of athletic prowess, heartwarming underdog stories, and inspirational triumphs of the human spirit. It has also given us stories of corruption, greed, and abuse that would make any person question how the sport has survived this long relatively little regulation. Every story that has shaped the world of college football as we know it in 2025 has had an equal part in creating the wonderfully flawed spectacle that puts hundreds of thousands of butts in seats, and millions of eyeballs on televisions. However, perhaps the biggest point of contention that has plagued the sport since its earliest days is the same one that haunts us today: What is a national ranking, and what is a national championship?

The Old Systems

Compared to the early days of college football, and even relatively recently in our modern eras, the system used to determine how college football champions are made is infinitely better. While college football has been around in one form or another since 1869, the first ranking system didn’t come about until 1936. That first Associated Press poll (a system that is still widely used today) was almost prophetic in illustrating the quirky flaws that frustrate fans and analysts to this day. The number one team and AP National Champion in the final rankings of the 1936 season was the 7-1 Minnesota Golden Gophers. The only loss by the team was suffered to the Northwestern Wildcats in 6-0 game in Evanston, but wins against four other Big Ten teams and a non-conference gauntlet that included Washington, Nebraska and Texas were enough to convince the voters that Minnesota was the best team in the land.

The major problem with this, of course, was the fact that three other major teams in the country finished the season undefeated. Santa Clara was the only truly undefeated team at 7-0, winning notable games against Stanford and Auburn, while losing to TCU and beating LSU in the Sugar Bowl after the final AP rankings had already come out. LSU themselves were undefeated in the regular season at 9-0-1, tying Texas in week two and their postseason loss to Santa Clara coming after the end of the season. Alabama also finished technically undefeated 8-0-1, with their only blemish at any point in the season coming in a 0-0 tie against Tennessee. You just don’t see final scores like that anymore.

With three other teams in the country scoring more wins than Minnesota, and eleven other ranked teams scoring the same number of wins (including the 7-1 Northwestern team that had beaten Minnesota), several other systems named other national champions that year. No fewer than sixteen national championship ranking systems were used to determine a champion (nine of which were used at the time, seven of which were applied retroactively), with Minnesota (x9), Pittsburgh (x3), Duke (x1) and LSU (x3) all being able to claim national championships that year. The legitimacy of national champions and rankings at any rate have always been a point of contention, and have always left doubt as to what actually makes a team worthy of being considered champion.

The “Poll Era” of college football lasted from 1936-1997, with the split-decision national championships ending with the adoption of the Bowl Coalition in 1992, granting significantly more credence to national championship claims. If you know anything about college football, however, you know that it is never that simple, and the obvious solutions are never the ones that are used. The Bowl Coalition had strengths in having the allegiances of the Cotton, Fiesta, and Orange Bowls in the championship tier (with three other lesser bowls played as part of the system as well), and had buy-in from most of the conferences in college football, including the ACC, Big East, Big 8 (today Big 12), SEC, and the SWC (which has mostly been absorbed into the Big 12). The big problem was lack of buy-in from the Rose Bowl, and subsequently the Big Ten and Pac-10 conferences which had tie-ins to the Rose Bowl Game. The Bowl Coalition was replaced by the Bowl Alliance in 1995, and ran into the same problems.

It wasn’t until 1998 that the Bowl Championship Series (BCS) appeared, granting our first system that included all major “New Year’s Six” bowl games (Rose Bowl, Orange Bowl, Sugar Bowl, Fiesta Bowl, Peach Bowl and Cotton Bowl, in no particular order), and all of the era’s power AND mid-major conferences. With every major entity in the sport represented, the system was able to use a combination of polls and computer rankings to determine the top two teams in the nation that should be worthy of competing in the BCS National Championship Game. And everything went off without a hitch. Obviously.

As you can imagine, the same biases and egos that tainted the championships of the Poll and Bowl eras of the sport existed in the BCS just as deeply as they had done before. If you you look up the wikipedia page of the BCS, the wikipedia page of “Bowl Championship Series Controveries” is nearly as long. Thirteen undefeated teams from 1998 to 2012 were left out of the BCS national championship game. A good number of those teams were from non-power conferences, coining the term “BCS Busters” for teams that beat the system that was perceivably rigged against them. Of those, Utah and Boise State were perhaps the most famous, being able to claim national championships from just winning their bowl games and not the BCS National Championship Game. The problems became so pronounced in the system that federal government at numerous points held that the BCS violated the Sherman Antitrust Act, with everyone from the Harvard Law Review to the US House of Representatives wanting a piece of the action.

Eventually, the BCS gave way to the College Football Playoff system in 2014, which began with four teams, and expanded to twelve teams in 2024. In an interesting twist of fate, the National Champion in the first year of both the first season of the four and twelve team systems were teams that would have been excluded from the playoff in the previous system, and were Ohio State both times. The playoff system was immensely popular, being repeatedly called for by fans and pundits alike for decades, if not an entire century. College Football was, of course, the only NCAA sport without an officially recognized national championship playoff.

Interestingly enough, the NCAA itself was literally created in 1906 specifically to reform college football rules to prevent onfield deaths, but the popularity of football as opposed to other spectator sports led to more problems. You can read thousands of other articles that address those problems, but those aren’t the point of this one. The point is, this is the system we have, and until it is inevitably expanded again, this is what we have. As always, there is the right way to do things, the wrong way to do things, and the way things are done. Our goal here isn’t to address the way things should be done, but rather to think about how things are done and how the flawed system ought to operate within its framework.

The Current System:

Today, the College Football Playoff and its associated rankings are decided by a thirteen member committee, most of whom are current or former athletic directors, coaches, players, and writers. Members serve three year terms, with a rotation of members representing every power conference, and some mid-major conferences. Fun fact: former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice was one of the original members of the CFP Committee. The Committee typically releases its rankings on the first Tuesday of each November, with the intention of doing it late so that they are influenced by preseason AP and Coaches Polls as little as possible. It is notable that the AP Poll, Coaches Poll, and any computer rankings are intentionally left out of the equation, leaving the Committee themselves to assess the quality of teams based on their onfield play.

The Committee selects their rankings via secret ballot, operating primarily in the form of a tier system, with six teams to a tier. While ballots are secret, debate is open, and the process is repeated every week until the end of the conference championship week of college football play. While strength of schedule and strength of record is the strongest point that influences the views of a team, the Committee is also free to look at things like injuries and even the weather and how they influence a team over the course of any given season. While it is a refreshing change of perspective compared to the “horse race” nature of the AP Polls and the overly formulaic computer rankings, it does give way to the question of what the Committee members are actually assessing: which teams are best teams in the country, or which teams are the most worthy of a spot in the playoff?

The best examples (before this year that is) of this came in 2016, 2017 and 2023, all three during the four team era. In 2016, the major controversy came from the Big Ten. Penn State had finished the regular season 10-2, which while technically inferior to the 11-1 record won by Ohio State that year, both teams finished 8-1 in Big Ten conference play. Penn State had defeated Ohio State in their head-to-head matchup that season, giving the Nittany Lions the tiebreaker that let them into the Big Ten Championship Game, where they defeated the Wisconsin Badgers 38-31. Despite winning the Big Ten Championship via the agreed upon rules of the Big Ten and besting Ohio State on the field, the Committee decided that Ohio State had a stronger record despite not winning a conference championship, and determined that they should be in the top four over the Big Ten Champion. Penn State narrowly lost to USC in the Rose Bowl that season 52-49, and Ohio State was blown out by Clemson in the CFP first round 31-0, which meant that the controversy doesn’t live on very strongly in the minds of the public, but it was very controversial at the time.

2017 was the best equivalent that the CFP era has to a “BCS Buster”, where the American Athletic Conferences Central Florida Knights completed a perfect regular season at 12-0 including a ranked season finale win against archrival USF, and a conference championship win in a double-overtime game against ranked Memphis. The 2017 CFP Committee declined to include the UCF football team on their playoff top four, but did allow UCF to compete in the Peach Bowl against Auburn. Interestingly, the recognized CFP National Championship that year was won by Alabama, whose lone loss that season came at the hands of Auburn in the Iron Bowl. UCF defeated Auburn in the Peach Bowl, getting a New Year’s Six Bowl win, and not only a claim to a National Championship, but a transitive one as well. The Committee never ranked UCF higher than 12th.

Last but not least, the final year of the four-team iteration of the College Football Playoff in 2023 saw a similar situation to what UCF experienced, but in the form of a power conference program getting left out. Florida State that season was led by head coach Mike Norvell to a perfect 13-0 regular season and ACC Championship. It seemed unfathomable at the time that an undefeated power conference champion would be left out of the CFP unless there were four other undefeated teams that played tougher schedules. When the final CFP rankings were released to set the bracket, however, Florida State was left at number five, just outside the Playoff. The Committee members’ rationale ranged from blaming FSU’s many injuries, including to starting quarterback Jordan Travis, go FSU’s 55th ranked strength of schedule. Ultimately, the Committee determined that their obligation was not to put the four most deserving teams into the College Football Playoff who had earned it on the field, but to the teams they thought would be the best four for the Playoff.

Florida State did play number six Georgia in the Orange Bowl that year, but the team evidently did not view it as an opportunity for a National Championship the way that UCF had six years prior. A mass exodus of Seminole players into the transfer portal came just after the rankings were released, leaving them shorthanded for the Orange Bowl, where they were defeated by Georgia 63-3, the largest Bowl Game blowout in the history of college football.

From an entertainment perspective, the Committee was clearly absolutely correct not to include Florida State. The team was a shell of its regular season self in the late stages of the season, and the ACC itself that season was easily the weakest of the power conferences that year. However, the implications of the decision were completely antithetical to the purpose of the Committee and the Playoff as a whole, and made the four team system untenable moving forward. Largely because of the controversy surrounding Florida State’s exclusion from the CFP (right or wrong), 2023 would be the last year for the four team system.

2024 saw the introduction of the twelve team system, which eliminated (so we thought) the chance for truly worthy teams to be denied an opportunity to win a National Championship. Initially, the top four ranked conference champions (not just power conference champions) would be given a first round bye, and the first round games would be played at on-campus venues. The Committee did away with the automatic byes for conference champions in 2025 after Boise State was able to win one from the Mountain West, but the top five ranked conference champions still retained the right to an automatic qualification into the Playoff, meaning that mid-major group of five conferences finally had a legitimate seat at the table.

During the BCS era and throughout most of the four team CFP era, a good argument could be made that there were not more than four teams in the country that were truly capable of winning a National Championship. You can look no further than the list of CFP National Championship matchups to see this exemplified, with some combination of Alabama, Georgia and/or Clemson appearing in eight of the ten title games during the era. However, the introduction of the transfer portal changed this. The ability for top talent to redistribute itself among teams across the country allowed for the number of truly elite teams to skyrocket, and introduced a level of parity in college football that had never been seen before. No longer could Nick Saban and Dabo Swinney stockpile all of the nation’s elite talent. When players can leave at any time to find playing time, NIL money, and better potential opportunities in whatever form they may take, the inherent advantage that those programs held was suddenly reduced.

So how does the College Football Playoff Committee choose their twelve teams?

According to the College Football Playoff Selection Committee themselves, the criteria for “distinguishing among otherwise comparable teams” includes:

Strength of Schedule

Head-to-head Competition

Comparative outcomes of common opponents (without incenting margin of victory)

Other relevant factors such as unavailability of key players and coaches that may affect team performance.

Past that, however, the criteria of what makes a team worthy of the CFP is vague if not completely implied. We would assume that strength of schedule would be reinterpreted as strength of record, as the most important factor in determining teams is and should be wins and losses. This, however, is made more difficult by the fact that power conferences are expanding, weakening the general strength of conference schedules, and power teams are scheduling fewer power conference opponents in their non-conference play. This means that there will be fewer distinguishing factors across conferences, making it more difficult to assess the strength of each. Media outlets may assume that the SEC is still the strongest conference in the country, but the inaugural twelve team College Football Playoff told a different story. Those assumptions about the strength and weaknesses of certain conferences are, of course, what prompted the creation of tournaments that would eliminate the need to rely on those biases to choose teams.

The job sounds simple, but in truth is very hard. With so much parity in college football, the best teams in the sport may vary from week to week. Take for example, the 2025 regular seasons of Alabama, Notre Dame, and Miami. For most of the season, Miami was ranked above Notre Dame after their opening week win against them. As Miami faltered down the road to unranked opponents, Notre Dame turned a 0-2 start into a 10-2 finish, putting themselves firmly in the ranks of the contenders. Alabama, who suffered an opening night loss to Florida State, saw themselves fall down the rankings after FSU was revealed to be a dud for the year. A loss to a solid Oklahoma team and a blowout defeat to Georgia in the SEC Championship saw them on the bubble. In one week, the rankings went from Notre Dame being ranked above Alabama and Miami, to below them despite the only material change to the situation coming from Alabama’s blowout loss, finishing at 10-3.

When the final CFP rankings of 2025 were revealed, Notre Dame was left out, and Miami and Alabama were kept in. It went over predictably poorly with the internet and the talking heads of the sports talk world as one would expect, but how did the decision come about?

Miami’s biggest advantage was their win over Notre Dame. In a world where wins are the biggest currency, this was a trump card. While Miami’s losses were unquestionably worse than the other two contenders, their win was significant enough to be worth noting over them.

Notre Dame’s biggest advantage was their margin of loss against Miami and Texas A&M. In both of those games, they lost by a combined four points. They rolled through the rest of their schedule, crushing ACC, Big Ten, and American opponents, but there were no major wins to speak of other than maybe USC.

Alabama’s biggest advantage was their strength of schedule, which was understandably prohibitive of a higher ranking than 9. Four ranked wins were more than either Miami or Notre Dame could produce, giving them a stronger resume despite more losses.

The information presented provides a relatively simple rationale for why Alabama was ranked 9th, Miami 10th, and Notre Dame 11th and out of the CFP. The majority of talking heads and the peanut gallery both have taken issue with Notre Dame being ranked ahead of both of those teams before the final rankings, and then being inexplicably leapfrogged at the last second. The truth of the matter is the rankings are completely pointless until the end of the regular season anyway, but the inconsistencies in the way that the rankings were seemingly compiled and presented have been conspicuous.

One solution to this would be not to release the actual CFP rankings until all conference championship games have been played. This projects an image of a shadowy cabal of college football tastemakers doing backroom deals with the movers and shakers of the sport, but in reality would protect the Committee from being influenced by public perception of their decisions. In the end, regardless of optics, the Committee will always be left with an impossible task based on mostly subjective data.

Other Championship Systems:

FCS Football:

When looking for solutions to the problem of deciding on a method for crowning a champion and determining what a championship caliber team is, it is hard not to look at the FCS Playoffs. With a college football playoff that has shown to be efficacious in producing legitimate champions over the years, it would seem that this is an obvious model by which to build on. Champions from ten conferences become automatic qualifiers for the Playoffs, while fourteen other at-large teams are awarded invitations based on strength of regular season resume. The FCS seeding system is somewhat convoluted itself, but the general idea is that the four sections of the twenty-four team tournament exist to crown regional champions who will then move on to determine a legitimate national champion. Currently, five of the ten FBS conference champions receive an automatic bid to the College Football Playoff.

European Soccer:

While the tournament model is used in almost every NCAA sport, and most other American professional and amateur sports, it would make sense to also review some other methods of selecting champions across different parts of the sporting world. European club soccer, like American college football for most of its history, decides a champion based strictly on regular season play.

Unlike in American football, there is a clear system by which teams are ranked, with a promotion and relegation system to trim a massive number of eligible teams to just twenty, speaking specifically to the English system. If your club wins, you get three points, if you draw you get one, and if you lose you get none. Tiebreakers are also simple, with goal differential and total goals being the decider. If there is a tie for a position that decides a champion or a relegation, there is a single neutral site playoff game. Other nations alter the system slightly, but this is generally how it is done.

Promotion and relegation is something that is frequently mentioned as a potential solution when discussing American college football, and conference realignment over the years has somewhat reflected the idea of promotion. However, getting schools (especially ones with hundreds of millions of dollars or more tied to their schools athletic programs) to agree to possibly be bumped to a lower division based on play is something that is not likely to happen.

Auto Racing:

While it may not seem like it makes a lot of sense to compare a sport where over a hundred teams can only compete against one other team at a time in twelve weekly matchups to one where anywhere from twenty to over sixty individuals compete against each other on one track at the same time, there are parallels that can be made. In most conventional championship models like Formula 1, IndyCar and IMSA, a number of points is allotted to each finishing position on the grid, and the winner at the end of the season is the driver and car that finishes the season with the most points. If there are ties, the number of wins is the ultimate tiebreaker. While it would be hard to award a number of points to FBS teams in this manner in a way that makes sense, you could conceivably differentiate the value of a single win based on your opponents wins and losses. Something similar is used in Illinois High School football (I only know this because I’ve coached at that level, and am not familiar with the systems that most other states use).

Nascar, however, is unique in that they use a playoff system to determine their champion. The most recent iteration of this playoff uses a 26 race regular season where drivers may qualify for the playoff with a win, or if they are one of the top sixteen drivers in points. After that, 10 more races are then run to whittle the field of playoff contenders from sixteen to four in the final race of the season. This system has been widely ridiculed and is being discontinued next season, but its emphasis on making sure that winning races was the largest determining factor in crowning a champion had its merit.

Since half of all college football teams can expect to win on any given week, simply winning a game is not a viable way to qualify for the College Football Playoff, but providing a number of wins accrued over the season required to be CFP eligible could be. For example, there are eleven teams in FBS this year that finished their regular season with at least eleven wins. This would provide opportunity to add at-large bids to keep the big money schools happy, and the emphasis goes to on-field play rather than to biased metrics like strength of schedule and strength of record.

International Sports:

International sports like the Olympics, FIFA World Cup and others don’t have the benefit of a regular season to determine who qualifies for their events, but they do have methods of ranking their participants. While there are different methods for determining how a team qualifies, the tried and true method for seeding teams for elimination play (or playoffs in American terms) is pool play. Teams are typically grouped into four-team pools, where they will play each team in their pool once to determine which of the four moves on to the bracket. In some cases (like in FIFA), there are methods for determining which teams can go into which pools, so that the strongest contenders are less likely to be pooled together. In other methods, groups are truly random and any team can be pooled with anyone.

College football conference championships used to function similarly to pools when they were small enough that every team could play each other in one season. Today, however, the most efficacious way to implement pool play into college football would be to create pools within each conference, and then to use them to form a conference tournament before sending that champion to the College Football Playoff. Some college basketball conferences use a similar system. The downside to this would be a reduction in the importance of interconference play, which provides exciting moments throughout the season for football fans.

Judged Sports:

In judged sports like gymnastics, figure skating and diving, points are awarded to competitors based on their ability to complete a task based on predetermined criteria and level of difficulty. I do not know how this system could be used to inspire change in college football, as it is inherently a subjective and unreliable method of determining a winner, and has been shown to be easily influenced by corruption and biases. The only reason I bring this system up is to compare it to the current system of determining the top teams in college football, which is also based on subjective and unreliable methods of determining a winner that are easily influenced by corruption and biases.

So what should be done with this information?

The Radical Idealist’s Solution

Every fan of college football is familiar with the problems that come inherent in determining the sport’s champion, and most have ideas for solutions. The obvious solution to the problem is one that would come with sweeping changes to the way the sport is played and formatted, which would rock the foundations of not only college football, but the American collegiate academic system to its core.

Dissolve All Conferences: All teams that participate must enter the season on an even playing field in order for the champion to be considered legitimate. Having one or more conferences whose teams are inherently ruled to be superior before any play has been completed delegitimizes the system. Conferences must be eliminated for the good of college sports.

Reduce the Number of Eligible Teams: At the very least, the number of FBS teams must be adjusted to a reasonable number. Teams should be classified into pools based on their performance in previous seasons. This can be done via a system of promotion and relegation so that elite teams only play elite teams, and so that growing programs are allowed to compete. Alternatively, all FBS teams could be classified into equal pools, where those teams will only play teams from their own pool for the right to compete in a playoff with other pool champions.

Give Scheduling and TV Rights Directly to the NCAA: Conference TV Deals have allowed the power conferences to force a corrupt and inherently inefficient system on college football that circumvents the authority of the NCAA and creates artificial castes within the sport. Allow a neutral party to determine the schedule, and remove the rights of individual universities and conferences to determine who, when and where they play, and on what channel it is broadcast.

Provide More Regulation over NIL Money and the Transfer Portal: A salary cap must be implemented for equality of opportunity among college football programs. A college football players union must be established to guarantee fair and reasonable payment for all college athletes, regardless of scholarship status, playing time, or program. Programs must be limited on the number of transfers they can receive per year.

Obviously, none of this is going to happen, and it also probably shouldn't. Something like this would require the dissolution of the entire American higher learning system. I’m sure there are a number of people who would like to see that happen anyway, but to do it in order to implement a fair College Football Playoff would be ludicrous. Even if it were to happen, the resulting system would be one that shares only a passing resemblance to college football. In many ways, the quirks and flaws of college football is what makes it unique and interesting. It’s not perfect, but it’s ours.

The Realistic Solution

Based on all of the provided evidence, there are simply too many factors allowed to play a role in determining college football rankings in order for them to be logically applied with fidelity. The current system allows bias to play too large a role, and objective metrics that we have access to are based on too small a sample size to be accurate and reliable. The only thing that can be determined objectively in a controlled environment without implementing sweeping destructive changes is Conference Championships.

Yes, conference realignment is something that has rocked the sport for decades and is reaching the point of insanity, putting west coast teams in the Atlantic Coast Conference and putting eighteen teams in the Big Ten. However, this is the only place where teams can have reasonable comparisons amongst each other with shared opponents. Regardless of what system a conference creates in order to determine their champion, each team in the conference goes into the season with an equal opportunity to win their conference, because the only thing that matters is beating conference opponents. Therefore, the only thing that should determine eligibility for the College Football Playoff is Conference Championships.

This solution raises a few concerns.

Concern: Haven’t conferences have become so large that teams can’t reasonably play each other in most seasons, making tiebreakers less effective? It also doesn’t provide a path to a championship for Notre Dame.

Response: The long term solution is acknowledging the fact that if existing in a large athletic conference or no conference at all doesn’t suit your school’s goals, then it would make sense for you to break off from your current way of doing things and form a regional conference that makes more sense for your institution. More conferences can mean more teams in the Playoff.

Concern: Haven’t there been many instances in which the top two teams in the nation come from the same conference? This system could eliminate the odds that these two teams are acknowledged as such and play in a championship game against each other.

Response: The simple solution to this problem is acknowledging that this isn’t a problem. The conference championship is the first step to winning a national title, you shouldn’t be able to do one without the other.

Concern: This makes nonconference games completely irrelevant. This eliminates a huge part of the sport where power programs and rivals across conferences can compete in games that matter to shape the landscape of college football.

Response: Yes, it does change the context by which nonconference games are played, but they would still be important to have in order to seed Conference Champions for the eventual playoff. Besides, rivalries don’t care about rankings.

Concern: This doesn’t fix the larger systemic problems in college sports. There’s still problems with money ruling the sport through TV deals, NIL and the transfer portal

Response: It isn’t supposed to fix those problems. This system still allows a large number of games to be played in the playoff for national TV audiences between passionate fanbases in iconic venues. It doesn’t address the bigger problems because we’re only here to make a truly legitimate National Champion a possibility for the first time in the history of college football.

Concern: This doesn’t fix the problems with subjectivity in the rankings. Every issue that exists within the current rankings system is still present despite this change.

Response: Actually, it does fix the problem with the rankings. It completely eliminates the need to have them at all. The AP and the Coaches will still have their polls, but they will no longer have any bearing on assessing the championship eligibility of a team.

Conclusion:

Is any of this relevant or helpful to anything? Will the powers that be see this blog post and think “Wow, this guy really figured it out” and fix the issues that everyone in the college football world plainly sees?

Probably not. The CFP is going to keep expanding. It will probably expand to at least sixteen teams this year, and will likely go even larger at some point in the near future. Every football fan with a phone or a laptop has their thoughts on how to “fix” or “save” college football, but the simple truth of the matter is that we love college football for the things that make it broken. “SEC Bias” and “Group of 5 erasure” are part of the game. They are parts of the game that we would like to address, but if they are going to be fixed, they should be fixed in such a way that allows fans to continue being fans.