The Pinnacle Problem

How Wealth Creates Talent and Prestige in International Motorsport

OTHER SPORTSMOTORSPORT

James Kemp

12/15/202531 min read

Note: This article was originally written on April 18th, 2024. Some statements in the article are no longer accurate due to recent developments in the motorsport world during that time. Since spring 2024, Max Verstappen and Lando Norris have won Formula 1 World Drivers Championships, and McLaren has won two Constructors Championships. Alex Palou has won two IndyCar Championships in record-breaking fashion, including an Indianapolis 500 Championship in 2025. An attempt has been made to make note of the changes that have happened since the original writing of this piece, but not everything has been accounted for.

Enzo Ferrari, one of the most iconic figures in automotive history, once said “Competition is the driving force of innovation.” These words were true long before Il Commendatore ever dreamed of a prancing horse, and have historically been true for almost every field imaginable; from science to art, or business to politics. It is no coincidence, however, that these words ring exceptionally true in the field that Ferrari helped to turn into the world’s most expensive sport: auto racing. In the world of motorsport, Enzo Ferrari is an iconic name largely because of his company’s connection to Grand Prix racing, which is what it was called in its formative days where Enzo actually drove, but has evolved into the discipline which today calls itself the “Pinnacle of Motorsport”: Formula One.

Fans of sports like Soccer or Rugby can watch their sport all year long in leagues around the world, and can observe their favorite athletes compete in diverse settings ranging from the club-focused regional leagues like the EPL or the NRL, or the truly international competition of events like the World Cup or the Olympics. Fans of sports like Baseball or Basketball which are played globally but have very clear premier club leagues like the NBA or MLB, have fewer options with which to compare their favorite athletes with the world’s best, but nonetheless are able to do it fairly satisfactorily. While there is frequent spirited debate on who the greatest athlete in each of these respective sports is, fans and pundits can easily turn to empirical evidence to support their claims.

Conversely, motorsport is the only form of athletic competition in which the only way fans can determine who is truly the greatest driver on the planet is by comparing them in completely different sports. While it is certainly a positive that fans of international motorsport have a unique experience among consumers of sport in that they have a seemingly unlimited catalog of ways in which they can enjoy it, this creates problems when trying to answer the question of who the greatest racing driver of all time, or right now is. In my previous paper The Partisan Paddock: An Exploration of Nationalism in International Motorsport, I explored the prevalence of the nationalistic tendencies and practices in nearly all organizational structures in the world of racing, and while I stand behind that work, it does not tell the entire story. In this paper, I will seek to complete this examination and criticism of the world of racing, by exploring the role of wealth in the world of motorsport, both in performance and perception.

Quickly recognizing my own bias, I am an American man in my late 20’s who was born in the state of Indiana. I grew up watching IndyCar and to a lesser extent Formula One, and have attended the Indianapolis 500 annually for over 20 years. I was raised in an era in which NASCAR dominated the motorsport conversation and zeitgeist in the United States, and therefore generally knew about stock car racing, but did not follow it until relatively recently. Today, I tend to be a significantly more egalitarian consumer of motorsports content, and have an appreciation for all of the forms it comes in. However, it is likely that I would not be writing this paper if not for my implicit biases, and therefore I must acknowledge them.

Racing fans who frequent message boards, reddit pages, or the social media platform formerly known as Twitter are frequently bombarded by questions such as “Who is the greatest racing driver of all time?”, “What is the most pure form of motorsport?”, “What is the most difficult form of racing?” or “What is the best form of motorsport?” Despite the obviously subjective nature of these questions, keyboard warriors and marketing professionals who tend to respond to those posts very rarely present their answers as opinion. Those connected to motorsports Reddit and YouTube circles are constantly exposed to this reality at a nauseating level. No shortage of arguments can be found in these comments either.

TheDuck33 of Reddits says: “NASCAR is top tier because they are the hardest cars to drive and drivers make more of an impact imo…I guarantee you put Lewis Hamilton in the 18 and Kyle Busch in the Mercedes, Kyle has far more success.”

A staff writer from Paddock Magazine added evidence to back his opinions: “Other forms of motorsport can argue, but F1 is at the top of the racing food chain. It has the highest speeds, the fastest laps, and the most powerful teams in motorsport: nothing goes faster around a racing circuit than a Formula One car. This isn’t cheap: F1 teams have annual budgets in the hundreds of millions of dollars, employ hundreds if not thousands of people, and build a new car every year.”

Drivers themselves are not exempt from voicing their opinions either. In 2021, former F1 and IndyCar champion Emerson Fittipaldi stated: “(The 2021 Indy 500) was incredible, for sure. I was talking to Zak [Brown], and I said what Indycar is doing is fantastic and much more exciting to watch than any other form of racing. It’s better than F1.”

As infantile as the “my dad could beat up your dad” type of questioning these examples provide, it is revealing. Fans of motorsport struggle to define what it is that they actually enjoy about motorsport, and the further into this endless black hole of cringeworthy yet arguable points one goes, the more obvious it becomes that feelings of nationalistic superiority in racing extends perhaps further in fans than it even does in manufacturers.

And who can blame them? There is no question what league is the pinnacle of Baseball or American Football, should it not also be this way in racing? And if your preferred form of motorsport is not the pinnacle of something then that must mean that your opinions are inferior as well. How can you possibly justify spending your valuable time and money on an inferior product? The same goes for drivers. How can you justify spending years of your life toiling at becoming a world class competitor if your competition is not world class as well? If it’s not the pinnacle of motorsport, why bother?

This question is arguably more important for auto manufacturers than it is for anyone else in the equation. Since the days when man first attached wheels to an internal combustion engine, the discerning buyer has always needed to find ways to differentiate between similar products. This problem is the basic one that all marketing attempts to solve, but unless they have a clear advantage, firms tend not to seek out head-to-head competition with their competitors. If there is a possibility of a clear loser, there is a possibility it could be you, and that risk is often not worth the reward.

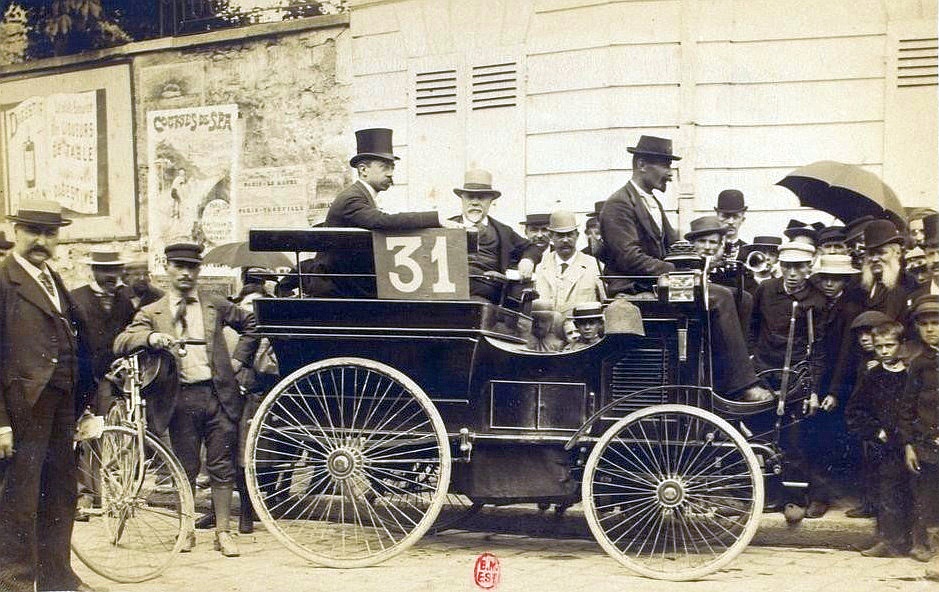

The history of marketing in the auto industry has always operated off of a different type of truth in this department, and therefore a careful examination of the history of mainstream automakers in motorsport is necessary. The automobile was invented in 1886 when Karl Benz applied for a patent for his “vehicle powered by gas engine”, and it only took until 1894 for the French newspaper Le Petit Journal to organize the world’s first known sanctioned auto race. The Paris-Rouen, as it came to be known, featured 102 entrants (of which only 24 showed up for qualifying) ranging from well known automakers from the period such as Peugeot, Panhard and Serpollet to private tinkerers who built their own machines. The diversity and innovation in these vehicles was also featured prominently, though only cars with petrol or steam powered engines actually showed up for the event. The winner would be the number 4 steam powered car of De Dion-Bouton driven by Jules-Albert, Count de Dion (the prominence of nobility in early European racing is also notable). The next eleven finishers would feature gas powered Daimler engines.

On the other side of the Atlantic, the public fascination with horseless carriages was equally as fervent, and the first sanctioned auto race in the United States took place a year later on Thanksgiving Day, 1895. Again, a newspaper was the featured sponsor, this time the Chicago Times-Herald, and again many entrants had filed their paperwork, but few showed up. The race actually had to be postponed from November 2nd due to issues with the course, and police stopping competitors as they entered the city, stating they “had no right to be on the street unless (they were) being pulled by a horse.”

Eventually the race did happen, and featured an interesting yet diminutive field of 6 (far fewer than the 80 that had paid the entry fee). Of those entrants, four were German vehicles built by Benz, one was a modified Benz, and one was an American built Duryea. It took nearly eight hours to trek the 54.36 mile course which stretched from downtown Chicago, north to Evanston and back south to the finish line on the campus which hosted the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893. The conditions: 30 degrees Fahrenheit and 6 inches of freshly fallen snow. The winner: Frank Duryea, driver of the sole American vehicle.

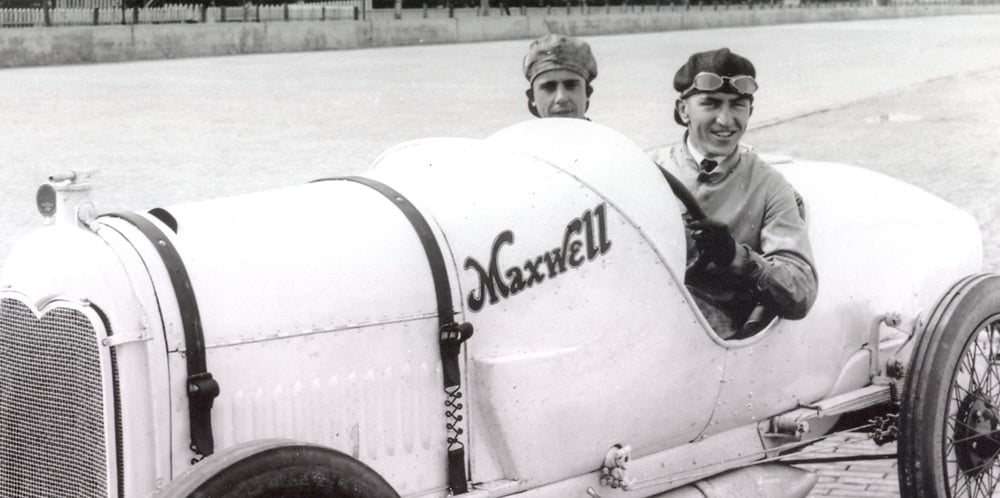

Racing in this era served a vastly different purpose than it does today. Competitions were not intended as contests of speed, but of reliability. By 1900, the automobile had developed significantly with speeds elevating from 7 mph to 50, and popular competitions such as the Bennett Trophy, Vanderbilt Cup and what would become the Indianapolis 500 pushed these vehicles to their limits. In these events, champion drivers like World War I flying ace turned racing driver Eddie Rickenbacker became folk heroes. While two World Wars would stunt the growth of the sport to a small degree, the inherent thrills and danger of the sport were evident. This was what drew in drivers and spectators, but the publicity was what prompted manufacturers to play along.

“Win on Sunday, Sell on Monday” became a common goal and rallying cry of automakers in the 1950s, but it had been present throughout the history of the sport, and remains present today. In that first decade of NASCAR racing, the most successful race cars included the Ford Thunderbird, the Hudson Hornet, and the Oldsmobile Rocket 88. It is no coincidence that those brands are also all represented on the shortlist of best selling car models of the 1950s. It is also no coincidence that the best selling non-SUV in the United States for over a decade has been the Toyota Camry, which has been a mainstay in NASCAR since 2007. Interestingly enough, European car entries were very common in the 1950s, but that 2007 Toyota debut was the first time we saw a non-American brand enter a Cup Series event since 1963.

Across the pond, trends differ a bit. American car culture had been shaped by the early affordability and accessibility of the automobile thanks to industrial developments from Henry Ford. The average American was able to afford a car and use it to commute from suburbs into urban employment areas. In Europe, the post-war economy prevented many people from being able to afford an automobile, and emphasis on public transportation made sure that cars remained a luxury product. For this reason, the manufacturers that were successful at Le Mans and in the early seasons of Formula One were not the best selling brands in European markets. With that being said, those brands that were successful like Ferrari, Mercedes-Benz and Jaguar were able to gain notoriety as luxury performance brands, rather than affordable economy cars.

The discipline that tends to stand apart as an outlier in all of this is the American open-wheel championship known colloquially as Champ Car, or IndyCar. After World War II, mainstream auto manufacturers (with the exception of Italian brand Maserati) practically disappeared from this discipline of the sport until the mid 1960s. The Offenhauser engine brand, which specialized in racing and marine engines rather than those of road going vehicles, dominated the sport from 1946 through the mid-60s. Almost all championship and Indy 500 winning cars in that period would feature those engines and a chassis built not by a large-scale manufacturer, but by small private racing shops. It wouldn’t be until 1964 when A.J. Foyt spent part of his championship season driving a Ford powered Lotus that we would again see recognizable brand names in victory lane. Coincidentally, this same combination of American power and British engineering would win two championships in Formula One in the late 60’s and throughout the 70’s as well.

The complicated nature of American racing continues when examining the equally complicated history of sports car racing in America. Post-War, the Sports Car Club of America (SCCA) would become the premier road racing circuit in the states, and while champions in its many categories of modified and production cars would almost exclusively be American drivers, they would include far more European manufacturers than American. The SCCA would eventually be surpassed by the International Motor Sports Association (IMSA) as the premier sports car championship in America in the 1970s, where German Porsche’s were so dominant that the organization introduced the “All American Grand Touring” championship category to try and encourage more American manufacturers to compete. Chevrolet had a long history of success in SCCA and to an extent in the early days of IMSA with the Corvette, but European sports cars were still the weapon of choice for most winning teams.

This postwar period of international racing is where the differences between the American and European theaters showcase differences in culture at their most obvious. For Americans, the dominant focus was clearly on building and modifying vehicles in order to compete domestically, with little focus on make and model outside of stock car racing, or in the AAGT class of IMSA. The large number of tracks that debut in that first decade such as Sebring, Daytona and Laguna Seca are indicative of this. Additionally, this is where the American market differentiates itself by retaining the “proving ground” legacy of motorsport through oval racing. While Europe did have ovals, and still do in some places, the medium never caught on to the degree that it did in the States.

In Europe, the presence of luxury manufacturers in racing led to a unique phenomenon of racing teams selling cars rather than major brands promoting their products. The most famous example of this would be Ferrari. The aforementioned Enzo would begin his career as a salesman and driver for the Italian marque Alfa Romeo, but would use those cars to form the now famous Scuderia Ferrari racing team. After disagreements with the company caused him to abandon Alfa, he began his own company in 1940, produced vehicles throughout World War II, and wouldn’t actually sell a single road car until 1947. Similar paths to entry would be taken by other companies such as McLaren, Lancia and Cooper, with the latter two no longer competing in racing on their own. (Note: Lancia has announced that they will return to racing in 2026 in the World Rally Championship.) This path was also followed by Chevrolet, but as the current flagship of the General Motors brand they no longer fall into this category.

For the most part, popular European consumer brands would not see a connection to racing success until later in their histories. The best selling brands of Volkswagen, Fiat, Renault and Opel (along with European models of Ford cars) would dominate the roads, while Porsche, Mercedes, Ferrari, Cooper, Lotus, and Aston Martin would dominate the track. In fact, while those same brands (with the exception of Cooper which would become synonymous with the Mini brand rather than its racing heritage) would continue to dominate in sports car categories in both hemispheres, Formula One manufacturer lineups more resembled the private garage builders of Indy as the 60s progressed.

As time progressed, it became less and less common to see overlap in the most popular forms of motorsport in the two hemispheres. Road racing remained dominated by the European makers, but outside of Le Mans you wouldn’t see many Americans racing in Europe or vice versa. For a time, it even became uncommon to see non-Americans compete in IndyCar or at the Indianapolis 500. On the other side of the open-wheel , while there have been fifty-eight American drivers to compete in Formula One, only thirteen of those have been since 1970, and only four since 1990.

It is during this time that the drivers begin to become more entrenched in their respective hemispheres as well. AJ Foyt, one of the most famous American drivers of his time and the first driver to win Indianapolis four times, had offers to race in Formula One, but had this to say about it: "I never cared about goin' Formula One racin' cause I was runnin' the sprints and the midgets and stock cars and everything here. And I always felt that the American people is what made A.J. Foyt, and I just wanted to race here. I was approached by a good team and offered big money, but I just blowed 'em off. Just forgot about it. Over there, you're like number one, two, three. So, say the number one driver is off a little bit, the number two driver, well, the way it used to be, you'd run second, regardless. And that to me isn't racin.' That's kind of barnstorm racin.' And I don't believe in it. And like I said, my name was made here and the American people is what made A.J. Foyt.”

This “that to me isn’t racin’” viewpoint is one that has been echoed by countless American drivers up to this day. Those who don’t see Formula One as a subpar racing product tend to blame its ladder system as creating an intentional barrier for non-European talent. Unlike in any other form of racing, Formula One requires its entrants to earn a “super license” from its governing body, the Federation Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA). In order to earn this license, a driver must score points based on their finishing position in their championship of choice.

These points are heavily weighted in favor of championships sanctioned by the FIA, such as the European Formula 2 and Formula 3 championships, which are exclusive feeders for Formula One. For an American to break into the sport, it is possible to earn enough points by winning an IndyCar championship, but it is highly unlikely that a driver would be able to find themselves in a position with a top team at a young enough age while attracting the attention of European teams. This theory has been echoed by California born McLaren CEO Zak Brown, who helms teams in both Formula 1 and IndyCar. “Because of the testing restrictions, it’s now difficult to take a driver out of America who maybe hasn’t been around these tracks,” Brown said. “The traditional route is you start in carts in Europe and you work your way up through the European Junior formulas, and we don’t have enough American drivers (there)…We only get three days of preseason testing, so you want a driver that knows the tracks, knows the team.”

(Note: A week before this article was released, the FIA released a new system which would provide more Super License points for IndyCar participants, but still significantly less than Formula 2.)

In reality, the major shift that separated Formula One from IndyCar in the early postwar days of nearly identical competition (beside ovals) was the change in costs. In America, the popularity of stock car racing led the nation’s top automakers to favor domestic racing, leaving smaller specialized outfits to compete in single-seaters. While sports car racing had and has its popularity all over the world, this popularity of stock car racing never existed in Europe, largely due to the difference in automotive culture among Europeans. This meant that while American manufacturers pumped money for their racing programs that intentionally limited innovative performance, European manufacturers did not.

The skyrocketing costs associated with Formula One competition are what followed, and few American manufacturers saw the benefit of promoting their product in markets where they were not active. In fact, there has never been an American factory team that has participated in the sport, even during the era of frequent overlap. (Note: American GM brand Cadillac will be starting in Formula 1 in 2026.) Today, both top level single-seater disciplines have introduced significant cost-cutting measures, but this trend is highly evident in the fact that while an IndyCar program can cost as much as $10 million per car, the F1 cost-cap is set at $135 million, and teams have spent as much as four times that before those measures were introduced.

This lack of desire to enter Formula One by American manufacturers has been distilled over time into a belief that American automakers and even drivers are incapable of making that jump. On the other side, Formula One drivers who won’t make the jump to the less profitable American circuits are either “afraid of being exposed by real racing” or “afraid of ovals”. Again we turn to social media as the representative of the vox populi, misspellings and all:

Nathan of Autosport.com writes: “I dont think GM is capable of designing and building a high technologicaly advanced race motor. They had tons of troubles with the IRL unit, then couldnt get Le Mans with the Auroura, same now with the Caddy, lets face it, GM has never really made anything close to what F1 demands.”

While the financial split between the American and European sectors of the automotive industry were more or less intentional, the corresponding ideological split in the world of motorsport may not have been. Regardless, the environment that exists now is one of perceived elitism, sectionalism, and nationalism. Until very recently, most American drivers had little interest in competing in European championships, and European drivers felt the same way about American championships. Despite the profitability of tapping international markets, the flow of sponsorship money and manufacturer funding further established a bisectional world of motorsport, and international politics tended to reinforce this as well, albeit possibly unintentionally.

This situation changed with the decline of NASCAR’s popularity in the United States starting in the late 2000s, and the acquisition of Formula 1 by the American mass media organization Liberty Media Corporation in the late 2010s. Since the IRL/CART split in the mid 1990s destroyed the popularity of open-wheel racing in the United States, NASCAR emerged as not only the preeminent motorsport category in North America, but one of the top three most watched sports in the extremely lucrative American spectator market. NASCAR had a span of over a decade as the only profitable sport in North American racing, and the goal of any young driver, team, engineer or patron that sought to “make it” would focus on the short tracks of Virginia and Tennessee and the superspeedways of Florida and Alabama. Names like Earnhardt, Gordon and Stewart had replaced those of Foyt, Andretti and Unser, becoming synonymous with speed in the United States. Meanwhile, while NASCAR experienced its peak of popularity, most American audiences were completely unaware of the landmark era of Formula 1 taking place across the pond with Michael Schumacher cementing his place as one of the greatest and richest drivers of all time.

Nothing showcases this split mentality quite as well as the 2006 Will Ferrell comedy classic Talladega Nights: The Ballad of Ricky Bobby. This film personified every stereotype that existed in the United States towards the sport of auto racing, from the Southern focused “redneck” and “blue collar” nature of stock car racing, to the snobbish and elitist nature of European circuits. The main antagonist, in fact, is a French Formula 1 driver who comes to America to showcase how much better he is than the “good old boy” Americans. Ricky Bobby and the Americans, of course, have never heard of Formula 1, and are appalled at every cultural difference which the French driver exhibits. While this is a piece of satirical fiction, the mindset it mocked was based on something very real, and the views on motorsport in the United States it showcased were more normal than some might like to admit.

In the late 2000s, NASCAR began to experience a decline in popularity following the introduction of new unpopular elements to the sport, and by the end of the 2010s was no longer present in the popular American lexicon. The reasons and causes for the decline of NASCAR have been studied at length and are worthy of examination in a separate paper as a landmark failure of sports marketing. By the time Liberty Media Corporation purchased Formula 1 in 2017, the American motorsport market was left without a true ruler, and was ripe for takeover from an outside force.

Immediately, Liberty focused the attention of Formula 1 on America. While Formula 1 returned to the United States in 2012 with the first US Grand Prix at the Circuit of the Americas, the US became only the second country to host three Grands Prix in one season by introducing temporary street circuits in Miami in 2022, and Las Vegas in 2023. Rumors have also circulated about the addition of a fourth circuit in a city like Chicago in the future.

While these events have seen solid attendance, the factor that has been given the distinction of blowing open the American market for Formula 1 was the 2019 Netflix series Drive to Survive. Being given yearly updates since the first season in 2019, this series follows the lavish and anxiety-inducing lives of Formula 1 drivers, exposing Americans for the first time to names like Fernando Alonso, Sebastian Vettel and Sir Lewis Hamilton. Also for the first time, Americans were exposed to the concept of the “Pinnacle of Motorsport”. While American motorsports fans of the 90s, 2000s and 2010s may have been insulated from the elitism of European racing that had been common in the 70s and 80s, this concept came screaming back as the world’s most expensive sport (not a title, a fact) finally became commonplace on this part of the globe. This new, flashy, and extravagant sport was now a hip trend for America's streaming youth, and while the average American in 2008 had likely never heard of Formula 1, the average American in 2024 can point out that it is competed by the twenty best drivers in the world.

These are all intentional and common slogans used by F1 media. “Pinnacle of Motorsport”, “World’s Most Expensive Sport” and “20 Best Drivers in the World” are not only phrases thrown around by media pundits, but have now entered the lexicon of the new crop of motorsport fans. These slogans are not dissimilar to those used by American series like the “Greatest Spectacle in Racing” used by the Indianapolis 500 and the “Great American Race” used by the Daytona 500, but while these statements are not new and would not be things that older F1 fans would necessarily see as false, this class of “DTS” fans have presented an exceptionally strong voice in social media, dominating the online conversation around motorsport. Before Drive to Survive, these slogans were around, but the average online American gave them even less credence than they would any conversation about European soccer. Now, these statements are being taken seriously.

Why these statements are now being taken seriously should not be all that surprising. NASCAR viewership has been dropping for decades, and hit its all time low in 2023. IndyCar has experienced modest increases in viewership since its rock bottom around 2013, but still averages around a million fewer viewers per race compared to NASCAR. Other series like IMSA are supported among niche corners of the American motorsports community, but sit nowhere near the popularity of the other two offerings. Formula 1 viewership in the States has reached similar levels to IndyCar, and is still not at the level of NASCAR, but the overwhelming presence of the sport on social media gives the impression that it has staked its claim in the American motorsports landscape.

While we have explored how nationalism and post-World War II economics created the cultural separatism of global motorsport, this desire for a de facto reunification prompted by Liberty Media has reintroduced what can be called the Pinnacle Problem. While the amount of money flowing into, out of, and around Formula 1 is unlike anything in any other form of racing, to call the drivers, teams and competition of Formula 1 the pinnacle of motorsport is dismissive of and ignorant to the key factors that gave it that station, and whitewashes financial and sociocultural inequalities between the participants. To try and solve the pinnacle problem, I will reignite the globalist spirit of competition from the early days of motorsport, and perform an analytical examination of the drivers, cars and overall circumstances of competition surrounding Formula 1 and its rivals to determine whether it is deserving of its self-appropriated titles.

Each part of the Pinnacle Problem can be organized by the slogans used by F1. First, the “20 Best Drivers in the World”. Of the three major slogans encompassing the Pinnacle, this is the factor that is perhaps the easiest to analyze. Drivers are the only piece of the equation that can easily be transferred between championships, and they do so quite often. Despite the extreme barriers to entry that Formula 1 places between potential entrants and itself, there are far fewer barriers to exit. Since 2017, 19 drivers have been removed from, or left their seat in the field of Formula 1. Of those, only Sebastian Vettel has gracefully retired with no obvious aspirations to compete in other sports. Kimi Raikkonen and Felipe Massa both were too old to attract the interest of a competitive team, and therefore were forced to take their talents to other disciplines of motorsport. Two drivers, Liam Lawson and Mick Schuamcher, are still active reserve drivers for F1 outfits. Every other driver was unceremoniously fired for lack of results.

Of those, most are still racing. Romain Grosjean, Marcus Ericsson and Pietro Fittipaldi have all made their way to the United States to compete in IndyCar. Of those, only Ericsson, a noted “Pay Driver” in Formula 1 who had zero podiums in 97 starts with the backmarker Caterham and Sauber teams, has experienced any success there with four wins in six years. Two, Daniil Kvyat and 2008 F1 World Champion Kimi Raikkonen, have also come to the US to try one-off NASCAR races. Neither has had any success. Three drivers; Stoffel Vandoorne, Nyck De Vries, and 2008 F1 Runner-Up Felipe Massa; all made their way to the all-electric Formula E championship. Of those three, again, only one has experienced any success. Stoffel Vandoorne, despite zero podiums in 42 Formula 1 Grands Prix, has had 3 wins in 75 Formula E starts, and was the 2021-2022 series champion.

Eight of the ousted drivers abandoned open-wheel racing for sports cars, five of whom landed in the World Endurance Championship. The other three, Nikita Mazepin, Jack Aitken and Sergey Sirotkin landed in smaller regional sports car championships. Of those WEC drivers, Brendon Hartley has been by far the most successful, scoring 21 wins with 4 championships in the LMP1/Hypercar category. Antonio Giovinazzi has had one win at Le Mans, but he along with the other WEC drivers have experienced no other success, and not all of them were featured in the top category of WEC.

The total tally of ex-Formula 1 drivers who have been successful in other disciplines since 2017 is markedly shorthanded. While we can confidently say that, since all of those 19 have to have competed in Formula 1 and very few have had any success against the other best drivers in the world, the statement that Formula 1 has the 20 best drivers in the world is demonstrably false. This is also historically the case as well, with most Formula 1 drivers never amounting to much with some going on to do great things either in the sport or outside of it. However, this does not necessarily mean that Formula 1 does not have some of the best drivers in the world.

Conventional wisdom would suggest that in order to qualify oneself for a seat in one of the 20 most prestigious race cars on the planet, one would have to prove themselves either with exceptional results in junior formulas, or be a champion in other top flight championships around the world. What would seem to be the most rational and obvious way to qualify oneself for Formula 1 is to become champion in Formula 2, previously known as GP2 and Formula 3000. From 2013 to 2022, every champion in GP2 and starting in 2017 Formula 2 has started at least one race in Formula 1. Felipe Drugovich and Theo Pourchaire, the champions from 2022 and 2023 respectively, both still compete in Formula 2 and are reserve drivers in Formula 1. However, of the current 20 drivers on the Formula 1 grid, only 6 are previous Formula 2 or GP2 champions: Pierre Gasly, Charles Leclerc, Nico Hulkenberg, Oscar Piastri, Lewis Hamilton, and George Russell. In fact, 7 of those 20 never even competed in a Formula 2 equivalent series. Some of those drivers came straight to Formula 1 from Formula 3, or were competing in other regional championships.

So if success in a near-equivalent series is not required to compete in Formula 1, what about success in other top flight championships around the world? Of the 20 current Formula 1 drivers, the vast majority have never attempted anything outside of a single-seater formula car on the F1 feeder ladder, and only two have ever won what could be considered a top flight event or championship. Both Nico Hulkenberg and Fernando Alonso have won the 24 Hours of Le Mans, the most prestigious endurance race in the world, and Alonso did it twice paired with a 2018-29 World Endurance Championship. However, both of those drivers achieved those feats during their Formula 1 careers, not before.

If we consider the top level of motorsport disciplines across the world, the series that could most accurately be described as top flight (or at the top of their respective feeder chains) that have even remotely applicable skills would be Formula 1, IndyCar, WEC, IMSA, and NASCAR. The series with the most applicable skillset to F1 would be IndyCar, and the last time an IndyCar Champion was offered a seat on a Formula 1 team was Juan Pablo Montoya in 1999, who won 7 races in 94 starts, and Jacques Villeneuve before that in 1995 who finished second in the 1996 championship, and won the 1997 Formula 1 Drivers Championship. While Villeneuve is not the only F1 champion to also win an IndyCar championship, Villeneuve is the only driver to win in IndyCar first. No champion from WEC, IMSA or NASCAR has ever been offered a seat in Formula 1.

Given the relative success of drivers like Villeneuve and Montoya, it would stand to reason that other series champions in IndyCar would likely possess a skill level to be able to compete in Formula 1, but this has not happened since the 90s. Also given the fact that Formula 1 teams uniformly have significantly higher budgets than IndyCar teams, it would stand to reason that it would not be hard to lure modern IndyCar drivers away from their teams with money. Clearly, success in previous motorsport endeavors is not the primary factor that influences whether or not a driver reaches F1. Something else other than skill must influence whether or not a driver is befitting a role in the pinnacle of motorsport.

While the concept of the “Pay Driver” is far from unique to Formula 1, the ability to contribute monetary funds to a team’s already exorbitant budget is just short of a requirement to secure a seat in it. This is not to say that pay drivers are characteristically devoid of skill, or that all Formula 1 drivers are pay drivers. However, the simple fact remains that motorsport is in and of itself an extremely expensive venture. Anyone seeking to enter the sport at any level in any discipline must have some level of financial backing. However, in order to secure a seat in Formula 1, which recruits almost exclusively from the European regions of its own support ladder, it is necessary to be a pay driver in at least some capacity. There are some successful drivers over the years who haven’t been pay drivers, but they are exceedingly rare. Additionally, this feature of Formula 1 racing has created a barrier to entry for not only talented drivers who lack the resources to compete in Europe, but also disproportionately to women and minorities. While these barriers exist in other disciplines as well, women have at least been able to compete in each of those other series, with notable efforts to increase the presence of women in those sports. With all of these factors combined, we can confirm that Formula 1 cannot reasonably claim to have the 20 best drivers on the planet, but certainly the 20 richest.

The second facet of Formula 1 supremacy that we will examine is the cars themselves. It is frequently stated that Formula 1 has the quickest and most sophisticated race cars out of any discipline on the planet, and for the most part this is true. While it is true that Formula 1 cars have never matched the straight line speeds of an IndyCar at a superspeedway, this is largely due to the fact that Formula 1 cars are built exclusively for circuit racing and IndyCars are built to be multidisciplinary. The amount of money, time, resources and people that goes into developing and engineering a Formula 1 car exceeds that of any other racing series in the world.

With that being said, Formula 1 is not the only racing series that has open development and enormous budgets. Prototype endurance racing has long featured the more consumer-applicable version of open race car development, and today frequently features budgets exceeding $100 million for Hypercar teams. The recent $135 million budget cap set in 2023 put toward Formula 1 teams may exceed this, but not by a particularly large margin when one considers how much of that money goes toward higher paid drivers, larger support staffs, far more races per season, and significantly higher logistical costs. The World Endurance Championship's Hypercar category and the IMSA GTP category are effectively identical, and both utilize the same vehicles in different championships being competed at the same time.

While the overall philosophy of WEC Hypercar design is fundamentally different from that of Formula 1, it is in no way an inferior formula of racing or engineering. While Formula 1 cars and prototypes may occasionally share some of the same tracks, and F1 holds lap records at nearly all of them, the purpose of the two disciplines have very little in common. F1 cars are intended to fit the traditional single-seater, open-wheel formula of car, navigating tracks of typically 3 miles or less for around an hour and a half at a time. Prototype cars are exposed to much harsher circumstances, with races ranging from 4 to 24 hours. Formula 1 cars as they are currently engineered could not stand up to the conditions of an endurance race, nor could prototypes compete in conditions of a Grand Prix. The same can also be said at any tracks which F1 may have shared with IndyCar or NASCAR. While a Formula 1 car may be able to match and far exceed speeds of both series on road and street courses, the same could not be said about ovals, especially longer superspeedways. Both American formulas are designed to operate at extremely high RPM rates for over three hours at a time, with low downforce features to help them reach higher speeds by minimizing drag. Formula 1 cars are designed with maximum cornering efficiency rather than top speed, and therefore could not likely succeed in it without mechanical failures.

While it is not an enormous stretch to suggest that Formula 1 has the most sophisticatedly engineered racing cars on the planet, this statement is completely ignorant to the differences in philosophy of competition concerning each individual discipline of motorsport. From a certain point of view, Formula 1 cars can be considered the quickest and most sophisticated in the world, but that point of view is still heavily reliant on the bias of opinionated perspective, and cannot be considered an incontrovertible fact.

The third factor that we can examine is the nature of competition itself in the discipline of Formula 1. Even to the casual viewer, calling Formula the most competitive racing series in the world is laughable. Since 2010, only four different drivers have won championships in Formula 1: Sebastian Vettel, Lewis Hamilton, Nico Rosberg, and Max Verstappen . Only two teams have won championships in Formula 1 during that same period: Red Bull and Mercedes, each winning seven times. The vast majority of those championships came with the championship driver winning over half of the races that season. In the most recent season, Max Verstappen won 19 of 22 championship rounds, clinching the title with five races remaining in the season. (Note: This changed in 2025 with McLaren's Lando Norris winning his first championship.)

Comparing this to NASCAR, a series whose spec formula is designed to create pack racing, there has only ever been one driver who has ever won over half of the races in a single season: Richard Petty in 1967. Today, NASCAR typically runs 36 races a season, significantly more than Formula 1, and only two drivers have won as many as ten races in a season since the year 2000. In the same period of time from 2010 to today that four drivers won championships for two teams, ten drivers won championships for six different teams, representing all four manufacturers that have been active in the series during that time. In IndyCar, there has never been a driver who has won more than ten races in a season. Similar to NASCAR, this is a spec formula series, but the cars are not designed to create artificial parity among cars. Since 2010, seven different drivers have won championships for three different teams, representing both of IndyCar’s engine manufacturers. An equally interesting statistic is how many different drivers win races each series per year. Looking at 2023 alone, fourteen different drivers won NASCAR races for six different teams, seven different drivers won IndyCar races for four different teams, and three drivers won races in Formula 1 that year for two different teams. In fact, only ten different Formula 1 drivers have won a Grand Prix since 2020.

With that being said, the subject of competition itself most closely showcases the differences in philosophy between American and European forms of motorsport. Both of America’s most popular forms of racing are spec series, meaning cars are designed to be similar to each other with little difference in performance between teams. While teams with more resources can still be expected to compete more consistently with better drivers, strategies and engineers, this is not anywhere near the degree to which this is true in F1. Formula 1 cars are constantly in development, with a rules formula that changes at least to a degree on a yearly basis. The true competition of Formula 1 is in the areas that are hardest for spectators to see. Engineers and car designers work tirelessly to develop updates for their cars throughout the season to try and gain an edge from race to race, and season to season.

While the difference in winners and championships has not been nearly as large as the American disciplines, the definition of competition is fundamentally different. While Formula 1 markets itself as a drivers championship similar to NASCAR and IndyCar, in reality, it is a constructors championship first. And while those constructors' championship results in F1 have been even more lopsided than the drivers' battles, these results do not reflect the development race that takes place behind the scenes. The fact that F1 teams typically have two drivers with a clear and enforced competitive hierarchy further emphasizes this fact. Unlike in other forms of motorsport, “team orders” are common where teams will direct teammates not to compete with each other, or occasionally to swap positions so the top driver can win races and score points for the team. While teamwork is not absent in other forms of racing, this form of micromanagement generally does not happen on this scale.

With a stringent examination of the drivers, teams and nature of competition in Formula 1, it is blatantly obvious that while the sport exhibits impressive features in all three categories, to call it the “Pinnacle of Motorsport” invites problems that do not stand up to logic. In reality, the “Pinnacle” is not a title of prestige, but a marketing slogan that is used to help differentiate the series from competitors for viewers. If this is the case, can any series co-opt the term for their own benefit? While my research could not find any active trademarks for the term, there is one factor that still exists that allows Formula 1 to retain the title: global popularity.

Viewership is the only indicator of prestige that cannot be dismissed with research and evidence. No racing series on the planet comes close to the number of viewers around the world that tune in to watch Formula 1 on a weekly basis. In areas of the world where there are fewer competitors to F1, this has been the case for as long as the sport has been televised. Millions of dollars go into marketing for the sport around the world in order to help prop up those numbers. While there are a small number of exceptions like the Indianapolis 500, this can also be said for the number of spectators that attend Formula 1 races around the world. Formula 1 remains the Pinnacle of Motorsport in the opinions of fans across the globe, and that is truly the most important differentiating factor that Formula 1 has. In the United States, Formula 1 still has not gained that distinction of monolithic popularity, but those in charge of its American expansion are making every effort to make it the case.

Until every young American race fan grows up dreaming of standing atop the podium in Monaco rather than Indianapolis or Daytona, the Pinnacle of Motorsport will remain whatever you want it to be. The name you equate with racing greatness; whether it be Schumacher, Senna, Petty, Earnhardt, Foyt or Andretti; will differ based on personal preferences. At the end of the day, racing is just like any other sport in that recognition of significance and greatness is entirely dependent on opinion. To stake an opinion on the matter is to invite discourse, and that discourse can only serve to grow passion. Because racing has had even illusions of globalization in the distant past, fans can point to names and eras as unequivocal cornerstones of history that cement their opinions as fact. Whether or not you accept the Pinnacle with all of its problems, the rich history and diversity of competition in motorsport remains a unique global phenomenon, and is one that is worth the time and effort it takes to fully explore and enjoy.

All Racing is Good Racing.